Multiple Vehicle Detection Utilizing Deep Learning Algorithms

This page is based on the following resources:

Report

Dataset

Code

Introduction

The principle and trend of deep learning based object detection models were reserached. Between the several models, two (RetinaNet and YOLOv5) were selected to be tested. In order to investigate the application of object detection in autonomous driving, a pre-labled on-road vehicle dataset was prepared. The dataset provided location and vehicle information of vehicle objects in each image. Accordingly, the object detection models were trained, validated, and tested. The resulting performace of each model was analyzed and presented at the end.

Overview of Object Detection

The task of object detection is to identify and localize objects within digital images or video frames which are basically a sequence of digital images. In order to detect multiple objects in one image or video frame, a training dataset has to provide both classification and localization information. Then, a object detection model trained with the dataset is able to properly detect where and what they were.

Object localization can be divided into two steps [1]. The first step is to generate a set of potential object proposals or candidate bounding boxes through a region proposal network (RPN). The proposals act as potential regions of interest (ROIs) that might contain objects. In the next step, bounding box coordinates of the proposals are refined to precisely fit the objects. It is achieved by bounding box regression. The model learns to predict adjustments or offsets to the candidate bounding box coordinates, adjusting their position, size, and aspect ratio.

Subsequently, the refined object proposals are fed into a classification network to assign a label or category to each object. The classfication network extracts meaningful features in the objects and calculates the highest probability of being mapped to one of the predefined classes.

Trend of Object Detection

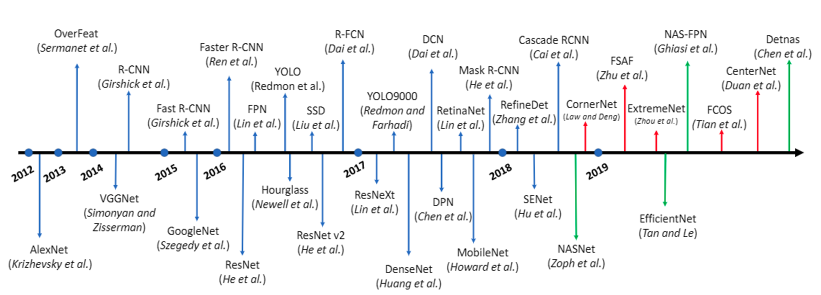

Fig. 1: Trend of deep learning based object detection algorithms [2].

Since 2012, various object detection algorithms has been developed as in Fig. 1. Main purposes of them is to improve accuracy, speed, real-time performance, and the ability to detect object at various scales [2]. Between the algorithms, Faster R-CNN, YOLO, SSD, and RetinaNet are dominant in autonomous driving [3]. In this application, accuracy and responsiveness are highly significant factors because autonomous vehicles have to identify other vehicles, traffic agents and signs correctly and promptly to decide their control and path. Obviously, the dominant algorithms demonstrate exceptional performance regarding the factors and has become used in the most of the autonomous vehicles’ object detection models.

Taxonomy of Object Detectors

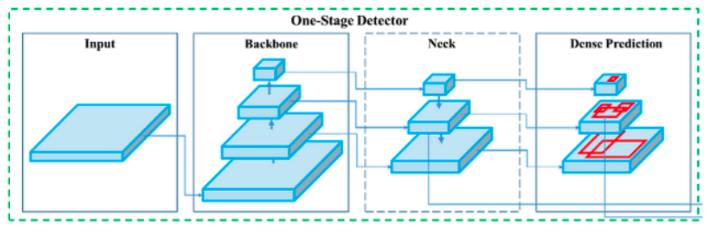

Object detectors can be classified based on their underlying network archituecture. There are two types of networks which are two-stage detectors and single-stage detectors. For example, R-CNN variants are two-stage detectors and YOLO, SSD, and RetinaNet are single-stage detectors.

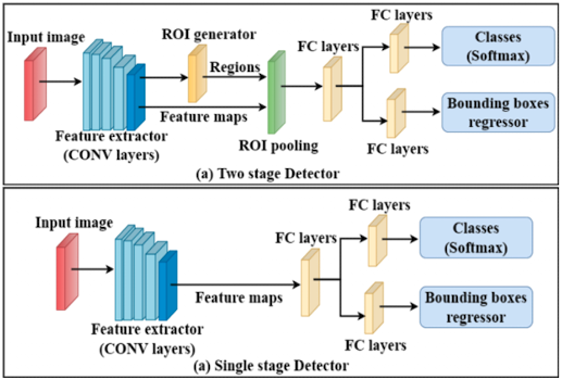

Fig. 2: Two-stage vs. single-stage object detector architecture [3].

Two-stage detectors use region proposal methods such as selective search or RPNs with image features from feature extractor using convolutional layers as shown in Fig. 2-(a). The ROIs are collected by a ROI pooling whose purpose is to extract fixed-sized feature maps from variable-sized regions. The ROI pooling aligns and reshapes the regions proposal into a consistent format for subsequent classification and bounding box regression. Fully connected (FC) layers are the final layers that execute linear transformation with weights in the network architecture. They provided a flexible and trainable framework for capturing high-level representations and making object-level predictions based on the extracted ROIs.

On the other hand, single-stage detectors directly predict class probabilities and bounding boxes in a single pass through the network as shown in Fig. 2-(b). Instead of using the ROI generator, they operate on a dense grid of anchor boxes that cover the spatial locations and scales of potential objects in the input image. At every anchor box location, similar predictions as in the two-stage detectors are implemented. The anchor boxes act as priors in the FC layers and their coordinates are adjusted along with the class and bounding box predictions.

The single-stage detectors are generally faster than the two-stage detectors due to their direct prediction approach. However, the two-stage detectors often achieve higher accuracy, especially for small objects or in cases with complex scenes, due to their multi-stage nature and refined bounding box regression. In the following sections, some of the detectors (RetinaNet and YOLO) were further explored and tested with a pre-labeled dataset.

On-road Vehicle Dataset

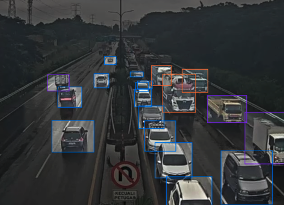

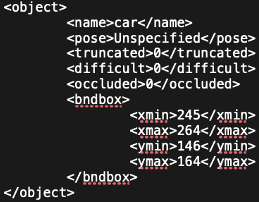

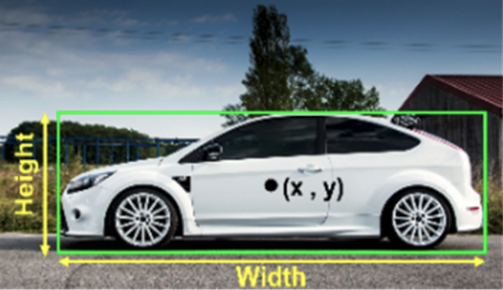

Fig. 3: Example of vehicle dataset.

The vehicle dataset was obtained from Roboflow which was a computer vision platform. It consisted of images of real roads where vehicles were driving and provided 2634 train set, 966 valid set, and 458 test set. The vehicles in Fig. 3 were classified into one of the 12 classes which were big bus, big truck, bus-l-, bus-s-, car, mid truck, small bus, small truck, truck-l-, truck-m-, truck-s-, and truck-xl-.

RetinaNet

RetinaNet is famous for its ability to address a class imbalance which refers to an uneven distribution of objects across different classes in a training dataset when detecting small objects which are common challenges for the single-stage detectors. The small objects have less features extracted, so RetinaNet uses a focal loss function during training and a separate network for classification and bounding box regression. The focal loss functions apply a modulating term to the cross entropy loss in order to focus learning on hard misclassified examples such as the small objects.

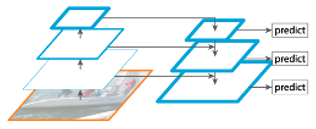

Fig. 4: RetinaNet Diagram [4].

The architecture of RetinaNet has a rich multi-scale feature pyramid from an input image and performs prediction at each scale as in Fig. 4. With such architecture, it can be semantically strong at all scales.

For the RetinaNet model training, Pytorch implementation of RetinaNet and Pascal VOC dataset format were used. In order to utilize sufficient computing resources, training and testing codes were run on Google Colab and can be found in this repo.

Fig. 5: Example of Pascal VOC format and its bounding box [3].

The Pascal VOC format was a xml file as in Fig. 5. The Pascal VOC format files included classes and coordinates of bounding boxes for each object in the images. 50 epochs were performed for the training. One epoch was when all the training data were used. The number of epochs was relevant to a convergence of weights of the models.

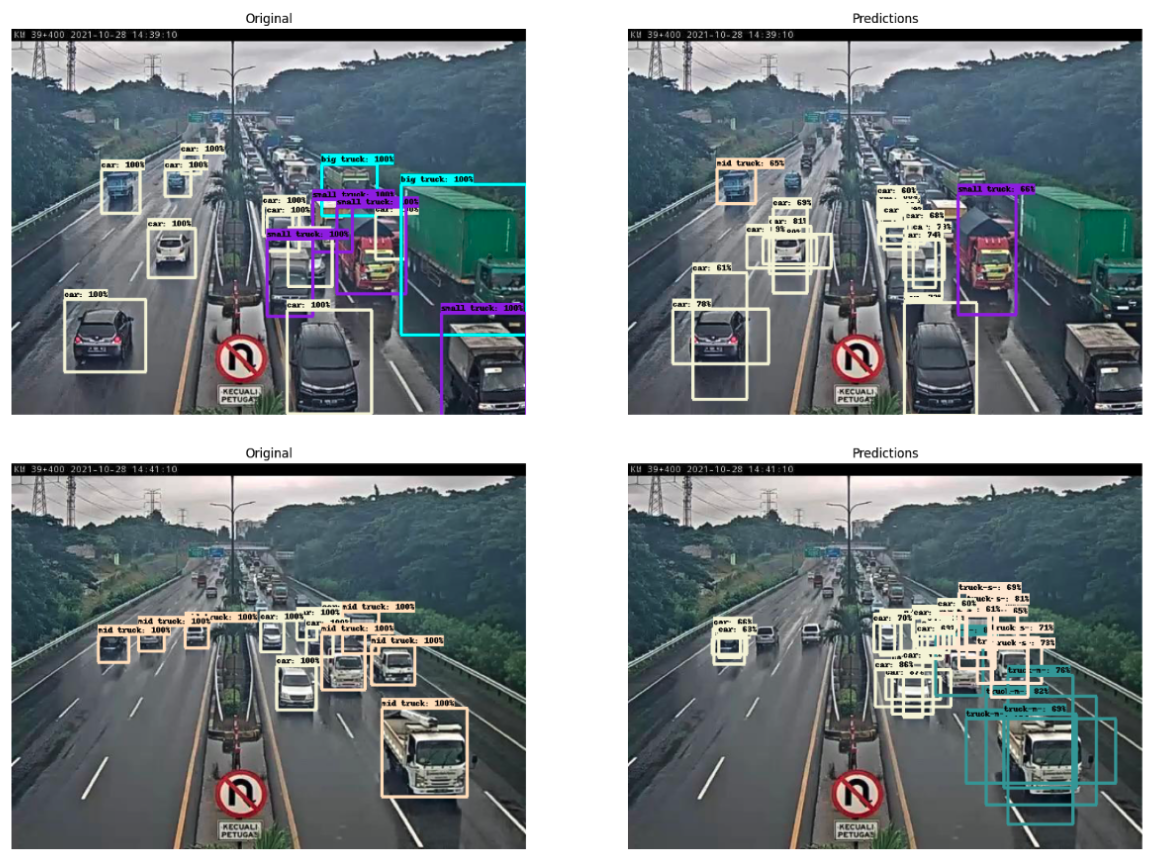

Fig. 6: Example of testing results from RetinaNet model.

The training result showed a classification loss of 0.112, box regression loss of 0.0385, and validation loss of 0.515. The classification and box regression were trained satisfactorily, but the validation loss was high which meant there was an overfitting during the training. Thus, the training results in Fig. 6 demonstrated some misclassification and duplicate bounding boxes on a single object.

YOLOv5

YOLO stands for You Only Look Once to emphasize its speed in object detection. It has many variants such as v1, v2, v3, and so forth. For the testing, YOLOv5 was selected since it was one of the latest versions and proved its performance on many datasets throughout open source communities. YOLOv5 is famous for proposing further data augmentation and loss calculation improvements. Data augmentation is deliberately transforming training images by cropping, resizing, and flipping to increase the diversity of the dataset. This improves the model’s generalization ability and robustness. Additionally, auto-learning bounding box anchors are featured in the detector to adapt to a given dataset. Anchor boxes are usually fixed boxes for calculating bounding boxes. Auto-learning bounding box anchors are adaptive to datasets in order to enable fast converging bounding box calculation.

Fig. 7: YOLOv5 Diagram [5].

The architecture of the detector is similar to that of RetinaNet having a rich feature pyramid to generalize to objects better on different sizes and scales and predicting classes and bounding boxes at each neck layer in Fig 7.

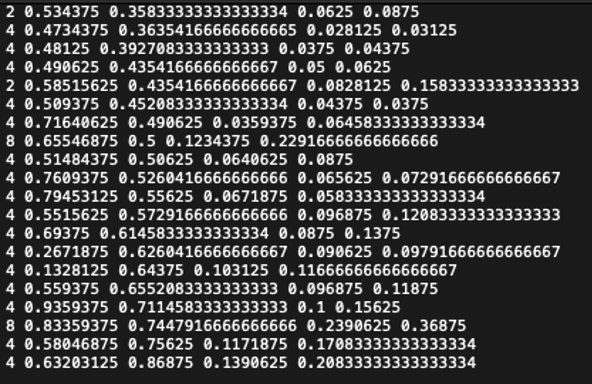

For the YOLOv5 model training, YOLOv5 model from Ultralytics and TXT annotations dataset format were used. Training and testing codes were run on Google Colab as well and can be found in this repo.

Fig. 8: Example of TXT annotation dataset [3].

Unlike the Pascal VOC format, TXT annotation format included class types and center coordinates of bounding boxes with their widths and heights. Again 50 epochs were executed for the same dataset.

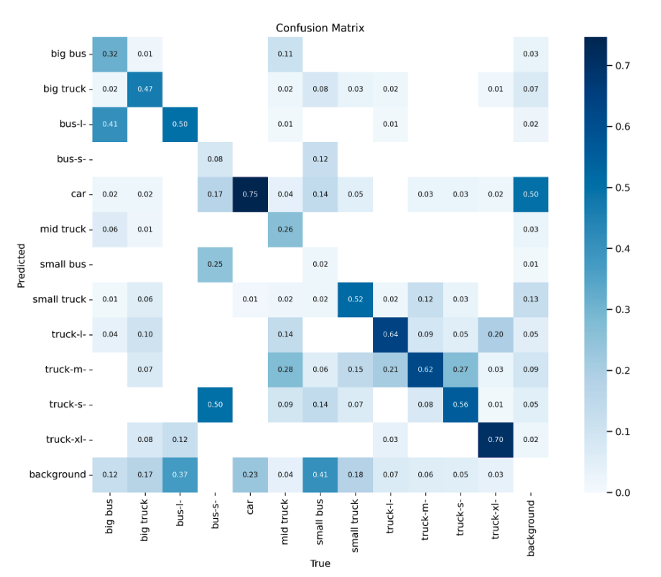

Fig. 9: Confusion matrix of YOLOv5 model on vehicle dataset.

The YOLOv5 model from Ultralytics provided not only training losses, but also various training results such as the confusion matrix in Fig. 9. It was able to make correct detections on most of the classes with a classification loss of 0.0069 and box regression of 0.032. Its validation loss was 0.036.

Fig. 10: Example of testing results of YOLOv5 model.

The YOLOv5 detected objects very accurately on the testing images as shown in Fig 10. Most of the vehicles were classified correctly and bounding boxes were fitting to them accurately. Even some vehicles that were partly occluded by other vehicles were detected showing the strong inference of the detector.

Conclusion

Table 1: Performance comparison between RetinaNet and YOLOv5.

| Object Detector | mAP | Inference Rate (fps) |

|---|---|---|

| RetinaNet | 10.6% | 71 |

| YOLOv5 | 41.1% | 129 |

The main performance indicators were mAP (mean Average Precision) and inference rate. mAP was a commonly used metric as it combined the concepts of precision and recall to assess the accuracy and effectiveness of an object detector. It measured how well the detector localized and classified objects across different classes and different levels of confidence thresholds. A higher mAP indicated better object detection performance. Inference rate was literally how many images a detector could process in a second. There was an overfitting issue with RetinaNet and it resulted in worse mAP than that of YOLOv5. However, they both achieved high inference rates as their architectures were single-stage detector. As long as the overfitting issue with RetinaNet was resolved, it was confirmed that why the two object detection models were popular in Autonomous Driving due to their accuracy and responsiveness.

Future Work

In order to resolve the overfitting issue with RetinaNet, different training parameters can be tried and the dataset should be reviewed to see if there is any class imbalance. Additionally, several other stratagies such as early stopping, pruning, regularization, and ensebmling could be tried.

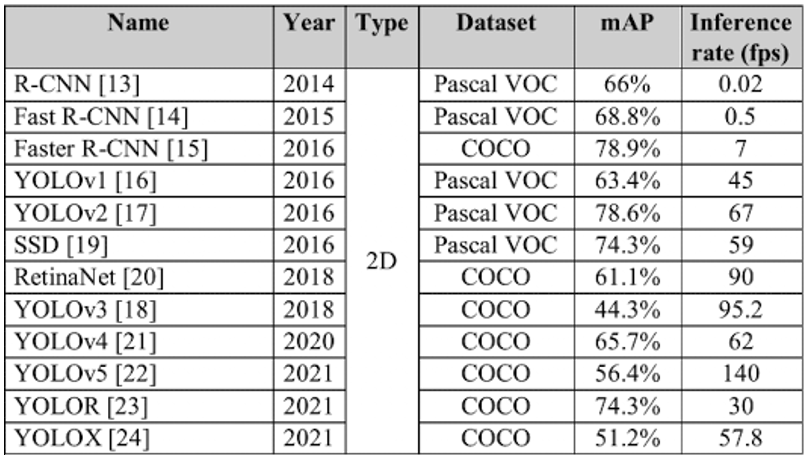

Fig. 11: Comparision between various object detectors that are commonly used in Autonomous Driving [3].

The performance comparision in Fig. 11 was used as a reference and trying each of the object detectors was desired to provide a thorough comparision especially depending on their architectures. For single-stage detectors, RetinaNet and YOLOv5 were selected and for two-stage detectors, Fast R-CNN and Faster R-CNN were selected. However, given the limited computing resource, it was taking too long time to train the two-stage models on Google Colab. The estimated training time was about 8 hours with 50 epochs and Google Colab was disconnected from time to time before finishing its task. Therefore, the two models can be tested with better GPU resources and reducing the testing image size and checking the right version of the required librarie such as tensorflow can be attempted.

References

[1] R. Shanmugamani, “Deep Learning for Computer Vision,” Packt Publishing, 2018.

[2] R. Sagar, “How the deep learning approach for object detection evolved over the years,” Analyticsindiamag.com, https://analyticsindiamag.com/how-the-deep-learning-approach-for-object-detection-evolved-over-the-years/ (accessed Jun. 20, 2023).

[3] A. Balasubramaniam and S. Pasricha, “Object Detection in Autonomous Vehicles: Status and Open Challenges,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.07706.

[4] A. Karaka, “Object Detection with RetinaNet,” wanda.ai, https://wandb.ai/site/articles/object-detection-with-retinanet (accessed Jun. 22, 2023).

[5] A. Bochkovskiy, “YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.10934v1.